My father’s parents both died before he turned ten years old. He essentially grew up as an orphan, and yet he was the happiest person I’ve ever known. At the age of seventy-nine, he simply refused to believe that the cancer eating away at his jaw would ever claim him. “A bump in the road” was the way he softly described the recurrence of his illness to me on the phone.

Five days before his death, he got out of his hospice bed, wobbling as he put on his pants, and announced that he needed to “go back to work.” I still believe he went to his death pissed off that he didn’t get one more day.

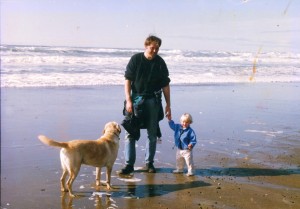

My former husband was raised by two of the most brilliant and charismatic parents I’ve ever known. They were movie-star gorgeous and equipped with languages and experiences I could only imagine. David traveled the world, ran a successful building company, and earned the most profound love of his life, our daughter. He skied, hunted, and fished. And he killed himself at the age of fifty-three.

What makes one person fight for every breath and another take his own life? Brain illness. There are a lot of theories about why people experience brain illnesses. In my time searching for answers, I’ve heard neurologists discuss disruptions in the brain while naturopaths point to an inflammation of the gut. I’ve seen behavioral therapists declare it is the result of a lack of meaningful relationships and a flawed, negative thought process. Psychiatrists talk about past traumas and a problem with chemical regulation.

I’m not a doctor, and I don’t pretend to know which of the disciplines will eventually be proven right, but I have a hunch. They are all right. As human beings, we are holistic beings. The interconnectivity of our genetics, our diet, our sleep patterns, and our past traumas create a delicate and sometimes disastrous dance. Everything I’ve read suggests resilience comes from a healthy lifestyle, meaningful relationships, experiences like yoga and mindfulness that draw you inward, and a dedicated perspective that allows you to believe things will get better.

My father’s body was racked with disease when he joked with me about who should control the remote. “From now on, I watch what I want,” he laughed. “I have cancer. You have to be nice to me.” When his oncologist flatly told him there had been a mistake on the tests and he’d better start putting his affairs in order, it was as if my father suddenly developed hearing loss. He refused to believe anyone was going to end his party.

David pulled away from us in the early stages of his brain illness and refused to share concerns about his lethargy, irritability, and confusion. He was, after all, a dignified man who rarely asked for help. When he was finally diagnosed with Bipolar II, it was as if his family, his work, and any semblance of a life that might have sustained him through his illness no longer mattered. He simply couldn’t bear the darkness that descended on his brain.

What mechanism allows one person to fight for every breath, even as their body is racked with a biological illness, and the other to end their life before they even get gray hair? I’d love to hear your thoughts.

“Look to the living, love them and hold on.” Douglas Dunn